Before the Internet age, publishing was a closed world to most people. Printing, binding and distributing books, magazines and newspapers required expensive equipment and resources. As a result, publishing your work meant getting approval from editors and accountants. Although “do-it-yourself” publishing became a little simpler with copy shops, digital tools really allowed self-publishing to take off.

Since we’re big fans of creatives making independent work, we put together this guide to getting started with self-publishing. Writers, designers, editors, reporters and artists will all find tips on how to prepare their material to publish online.

- What is digital self-publishing?

- How to publish a book online

- How to publish a digital portfolio

- Why make a flipbook resume

- How to create a magazine

- How to start a newspaper

- Optimizing self-publishing for social media

- Understanding your digital self-publishing audience

What is digital self-publishing?

Self-publishing is producing and distributing original creative work outside the traditional publishing establishment. In other words, self-published authors write, produce and distribute their books without the input and assistance of a publishing house’s staff. Even though self-publishing includes print formats, the industry’s explosive growth is mostly driven by online options.

One amazing benefit of self-publishing is that it makes expressing yourself easier than ever. Instead of being chosen by gatekeepers, creative voices are empowered to take charge of their own work. But if you’re not a novelist, don’t worry—online self-publishing is a perfect fit for all kinds of genres and media. Check out our tips for books, portfolios and résumés, magazines and newspapers below. Then, get inspired to self-publish your next great idea on Calaméo!

How to publish a book online

All over the world, lots of people dream about becoming authors. According to surveys, more than 80% of Americans feel they have something to write about. In France, over half of adults have written or want to write a book. If you’re an aspiring author, there are plenty of reasons to pursue your passion. Thanks to digital self-publishing platforms, sharing your work is simple and quick.

Writing

Of course, the first step is to write your book—and that might take a while! Whether it’s fiction, essays, poetry or research, give yourself the time you need to write a book you’re proud of.

Editing

Next, edit your work. There are two main kinds of editing. To edit for content, re-read your entire text and make notes about areas you’d like to change. This can involve small changes, like using a different word here or there. Or your editing might reveal big changes, like chapters to restructure. Either way, you may have to edit your book for content several times until you are happy with it.

Then it’s time for the second type of editing: copy editing. That means going over your text with a fine-toothed comb and fixing all of the grammar and spelling mistakes which snuck in while you were writing. And unfortunately, a run through spell-checking software isn’t reliable enough to produce error-free results. Despite being much more straightforward than editing for content, many people find copy editing challenging. It requires close attention to detail and good knowledge of language rules. Therefore, you may want to have another person help you copy-edit your text.

Formatting

Finally, consider how to format your book for digital self-publishing. In part, the right format depends on where you plan to publish your book online. For example, Amazon’s popular Kindle Direct Publishing service specifies different file formats for different types of content and access. On the other hand, Calaméo accepts a wide range of document formats. This is also when you should think about the cover for your book. Since the cover is the first thing audiences will see, it’s important to pick the design carefully. Bold illustration, eye-catching color and strong fonts are all fun ways to stand out!

Once you’ve finished writing, editing and formatting your book, you’re ready to publish. Log on to the platform of your choice and upload your masterpiece for readers to enjoy!

How to publish a digital portfolio

If you’re not sure that a digital portfolio sounds like self-publishing, think again. Creating and sharing a browsable selection of your work is a powerful way to represent yourself online. With some SEO basics and smart decisions, your portfolio can be the top result when people search for you on the Internet. Here’s how:

- Select your best work.

To put together a great portfolio, curation is key. In short, your most important job is to be critical about your own work. Because your portfolio shouldn’t include everything you’ve ever produced, focus on choosing the best. This might be pieces that have won prizes, received high marks, gotten positive feedback—or are just your personal favorites.

- Set up a structure.

Now that you’ve made a selection of pieces to go in your portfolio, find a way to organize them that makes sense to you. For instance, you could separate works by medium and have sections for photography, painting and graphic design. Or you could display everything in chronological order. Whichever organization you choose, be sure to make it clear to the reader with section breaks or a table of contents.

- Add links.

Using free tools like Canva or professional software like InDesign, you can save your finished portfolio in a PDF file format for digital self-publishing. Calaméo’s platform is free, simple to use and converts your PDF portfolio into an HTML5 flipbook in under a minute. Plus, you can easily add links that help readers learn more about your work. Point them towards your website, social media accounts or store.

- Publish and share.

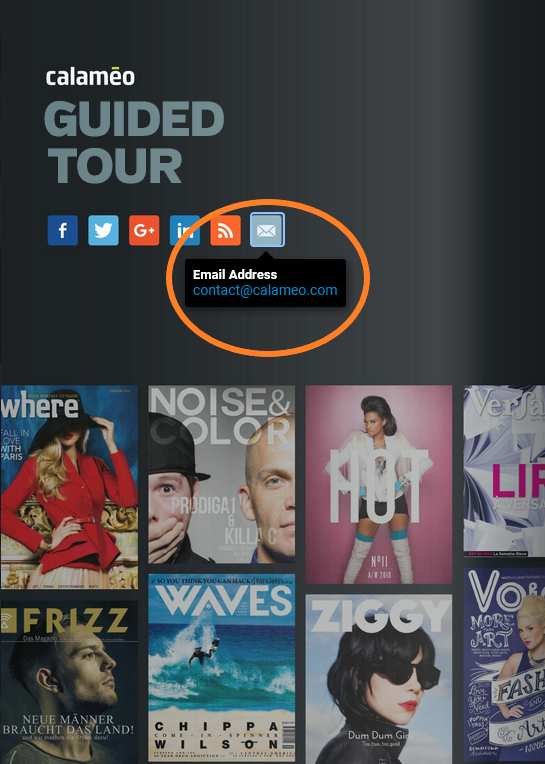

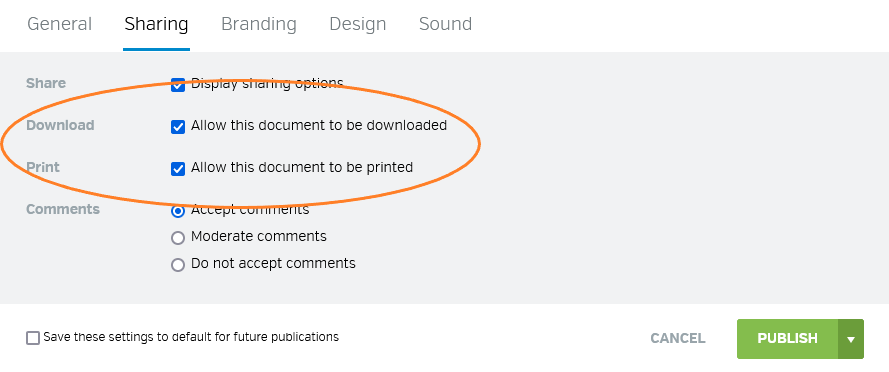

Congratulations—your portfolio is published online and looking good! Next, you’ll want to share it to build an audience for your work. For best results, Email the link, post to social media or embed on your own website.

And there you have it: a searchable, interactive online portfolio designed for browsing and optimized for follow-ups. Thanks to digital self-publishing, showing off your creative skills is a snap.

Why make a flipbook resume

Today, a digital resume is an absolute must for job-hunters. Indeed, the days of printing off a stack of resumes and hitting the pavement are a thing of the past. Almost all hiring is now done either through personal networks or online. As a result, creative candidates are finding ways to make their CVs and portfolios stand out from the crowd.

So why not join them and create a self-published digital resume for recruiters to consult? Rich media like interactive flipbooks can improve the quality of online communication. Plus, it only takes a minute to upload the PDF of your resume to Calaméo’s digital publishing platform. If you’re not ready to share with the world, publish privately and send the URL to selected viewers. For an all-in-one professional publication, combine your CV and portfolio into a single flipbook.

TIP: A contact button inside your portfolio lets people connect with you right away. Opt for an email button or voice call on mobile devices.

How to create a magazine

At Calaméo, we love magazines—and we love giving people our best advice on how to start a new magazine from scratch! To find everything you need to go from idea to launch, check out our detailed breakdown here. It’s full of lessons we learned when starting our own CALAMEO Magazine, which has been an amazing adventure for over three years now.

But in case you’re looking for just the main takeaways, these are the four essential tips to know about starting a magazine:

Be clear about goals

Be clear about goals. Creating a brand-new magazine is a big job and it can be difficult to resist getting sidetracked by all the decisions that need to be made. When you have clear goals from day one, those decisions become simpler. Before you begin thinking about deadlines and bylines, answer the following questions:

- Why do I want to launch a magazine? What do I want to achieve?

- What will my magazine be about?

- How often will I publish my magazine?

- Who do I want to work with to produce my magazine?

- How will I measure the success of my magazine?

Most importantly, remember that the answers should reflect your real goals. For example, getting lots of views might matter less than making new connections in your community. Write down your goals and refer back to them often!

Define team roles and schedule

Since you’ve already decided how many issues of your magazine to publish, the next step is to make a schedule. Although it doesn’t need to be exact, you should have an idea of the time you’ll have to create an issue. Then, communicate the schedule to the members of your team. We suggest having a dedicated Editor, Lead writer and Designer. But as long as you define what each contributor’s responsibilities are, you can set up your magazine’s creative team however you prefer!

Respect deadlines

We’ll be honest: this tip isn’t the most fun part of starting a magazine. However, it is key to making sure the vision becomes a reality. Especially for your first issue, keep yourself and your teammates on track by setting deadlines. And don’t be afraid to provide reminders when deadlines are coming up. Without a schedule, organizing the content, design and publication of your magazine will be much harder than it has to be.

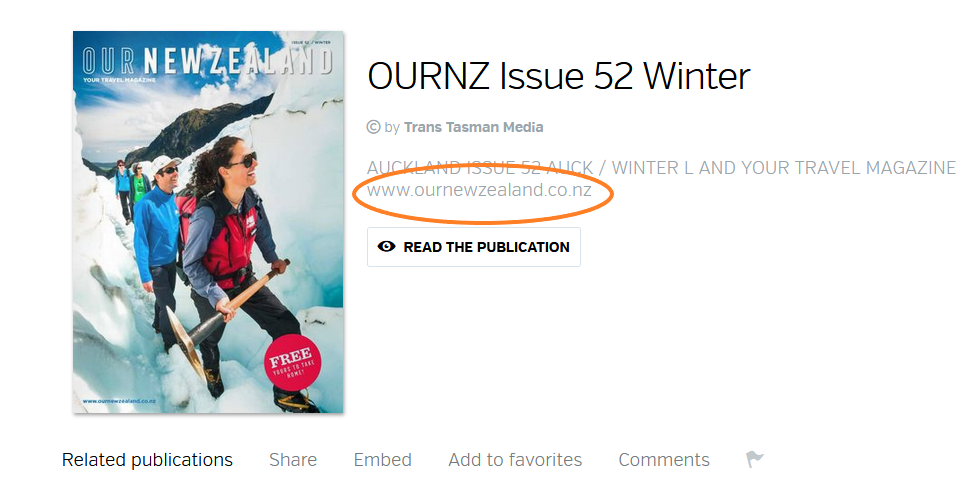

Publish online

Luckily for everyone, there are now easier ways of distributing your magazine than making photocopies for the local newsstand. Online self-publishing platforms help you to create a home for your magazine on the web. In fact, readers can discover and browse issues from anywhere—at home or on the go. Better yet, a digital magazine means big savings compared to print.

Have you been inspired by an independent magazine self-published on Calaméo? Let us know on Twitter @calameo. Or tweet us about your own magazine so we can check out the launch ourselves!

How to start a newspaper

Out of all the self-publishing formats, a newspaper is one of the most ambitious projects to start. Of course, there are thousands of independently published newspapers around the world that serve as an example. From city weekly papers to high-school extracurriculars, journalists everywhere produce their own newspapers.

Producing a newspaper is complex, but success depends on many of the same steps as for a magazine. In particular, a lot of hard work happens before writing and reporting begin. Similarly to magazines, decisions about goals, schedules and roles form the base for smooth teamwork. But unlike most magazines, newspapers usually publish at a faster pace. To create daily or weekly editions requires strong commitment and organization.

Also, self-published newspapers benefit from some specific tools. For example, creating newspaper layouts is much faster with dedicated software. While some options can be on the expensive side, there are a number of free online services to try, such as ARTHR. Whether you choose to print or to keep things digital-only, these tools will generate a high-quality PDF file for each new edition of your paper.

Finally, consider how to manage the archives for your newspaper. Obviously, the total number of issues and pages will vary according to how often you publish. To maintain an online edition, be sure to find a digital publishing platform that meets your storage and content management needs. Features like folders to group archives by month or year, virtual library widgets to create browsable archives and generous storage limits can help your newspaper thrive online.

Optimizing self-publishing for social media

Social media networks are a great place to share your self-published work online and find new audiences. When you’ve published on Calaméo, there are a few quick boxes to tick so that your posts look their best. But in general, key points to remember include:

- Match your content to the network. Professional publications might get the most response on LinkedIn, while lifestyle magazines are right at home on Pinterest.

- Offer a preview. For longer work, try creating a separate publication with just a few pages to share on social media.

- Focus on the visual. Your publication’s cover will be a big part of your post, so go for bold, bright design. If possible, preview to check that everything displays correctly.

- Write a great caption. It doesn’t have to be long, but your post’s text should be intriguing enough to make readers click!

Looking for in-depth pointers about social media? Our Digital Publisher’s Guide to Social Media has strategy ideas for Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn and more.

Understanding your digital self-publishing audience

A great reason to choose a digital platform for your self-published work is the access to audience statistics they can provide. Or to put it another way, online self-publishing means knowing more about who is seeing and interacting with your creations!

For a map to getting the most out of viewership statistics, check out our full guide to Analytics made easy. But to start with the basics, here are three ways that data can help you understand your self-publishing audience.

- Views.

Simple but important: how many times have your publications been viewed? Get more detail by looking at the Page views, which show how much of a publication your audience views.

- Location.

Thanks to digital platforms, access to self-published content is greater than ever. Because people worldwide can log on and discover your work, location data tells you the countries where your views are coming from. The results might surprise you!

- Time.

Reading time metrics give you insight into your audience’s engagement with your publications. The more time viewers spend with your content, the more it’s holding their attention! Plus, dive into which pages boast the highest reading times.

Now that you’ve learned all about digital self-publishing, all that’s left to do is to start creating! When your work is ready to share, you can publish it for free on Calaméo. Sign up for your account and self-publish your book, magazine, portfolio or newspaper online in just a few clicks.